Regulating communication

“The original telegram must be conserved for two years.” (Dresden, 1850)

Already, in the nineteenth century, Europe had identified the need for collaboration in the telecommunications field. So the Dresden Convention was signed in 1850. Four years after the first telegraph line was completed in Austria and Hungary, and shortly after Germany got done.

“In Europe, newspapers were also among the first and best customers of the telegraph. In 1850, Julius Reuter began his distribution of political, financial and economic news by his Reuter’s Telegrams. The collection and distribution of news across Europe had been made easier since the first telegraph line was completed in France in 1845; in Austria, Belgium and Hungary in 1846; in the Italian peninsula in 1847; in Germany in 1849; in Switzerland in 1852; and in Russia in 1853.

Source: 50 years of ITU-T, ITU 2006.

Tony RutkowskiP calls the convention “the first multilateral agreement dealing with telecommunications and regulated cross-border telegraphy”.

The treaty is still an interesting read, as it defines regulations which even today do not sound outdated. For example, it includes the order that the length of a message cannot exceed 100 words. This recalls similar restrictions for SMSG (which were set at 160 characters) and is still true for Twitter (140 characters).

Even to split the message and send it to the receiver straight away was only allowed if the lines and apparatus were not otherwise occupied. Article 14 is of special interest as it identifies an early version of “data retention”. In 1850, the instruction for providers was that the original message should be preserved for two years.

Good to know:

The Domain Name System (DNS) was invented in 1983 by Paul Mockapetris. The idea of it was included in Request for Comment (RFC) 882, which describes the technical development of computer networking.

Domestic regulations on correspondence remained untouched by this convention, and remained a purely internal government affair. The same was true for the system setup and equipment. As a consequence, messages needed to be translated at the border station. This was a pattern that was still in place more than 130 years later, when electronic mail was sent from the UK across the Atlantic, as Peter Kirstein recalls from the early 1980s:

The formation of CCITTG dates back to 1925, and the so-called Paris conference. After the Second World War, in 1957, it finally found its permanent home in Geneva. At the Plenipotentiary Conference in Geneva in 1992, CCITT was renamed the International Telecommunication Union (ITU-TG).

No trespassing

Formerly, PTTsG were government bodies. This special status lasted within the European Union until 1998 – a year that constituted an ultimatum for France Telecom, the last to be privatised. However, since the laying of the first transatlantic telegraph cable in 1858, telecommunications has been an international affair. Yet up until today, every government seems to favour its own industry foremost.

In the 1960s this behaviour was justified by local needs, as well as interest in exporting the equipment. But the latter never happened, as E.M. Deloraine from the Laboratoire Central de Télécommunications, Paris, France, wrote:

“Some of these national companies have financial or technical links, but this only avoids complete duplication and permits but a limited degree of technical coordination.”

Despite all local efforts, at the end of the day, the transmission systems of the various PTTs did not differ very much from those in the US. This was particularly true of the long distance coaxial and radio networks that form the backbone of European communications.

“The designs in practically every country are closely related to those found in the United States. We shall see also that most European switching system types were not duplicated in the United States.”

Source: E.M. Deloraine, Telecommunications in Western Europe, ITT magazine, 1965.

European nations had more than 40 manufacturers for switching equipment and over 60 companies producing loop cable in the early 1960s, but they all faced difficulty in expanding cooperative ventures outside their home countries. One might argue that they failed to cross Europe’s language barriers, but then continental Europeans had to learn English too, in order to co-operate with American partners. Most companies preferred to take that path instead.

New chaps on the block

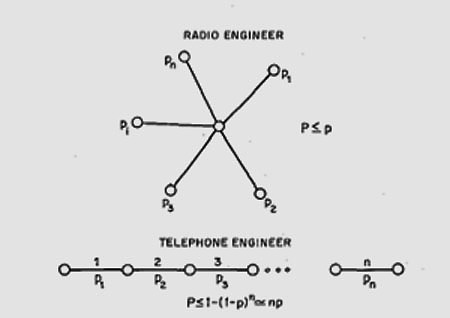

In the 1960s, the gatherings of the PPTs were driven mainly by tariff-policy on data communication and modems. But memos were also written, warning of the dangers of data network design as it was foreseen that this would bring their telephone networks down. In Europe the effect of all of this was that the work of computer scientists was considered evil and PTT managements ever more loudly praised the glory and reliability of their own engineers’ work.

One can not deny that a culture clash began to brew when computer scientists and PTT engineers first met. Especially as the PTT mind-set meant it was normal to stick with a product line for 40 years on average while computers were designed to be around for no longer than five. Little wonder then that not only PTTs but also European politicians avoided using the term “Internet” at all for quite some time. Instead, they preferred to talk about “value-added services”.

By taking a close look at today’s telecommunications and computing policies, one might add that we are on the way back along that particular path to a walled-garden policy, one of proprietary systems and “quality of services”, instead of the free flow of information.