How it all began

In the beginning was a beep

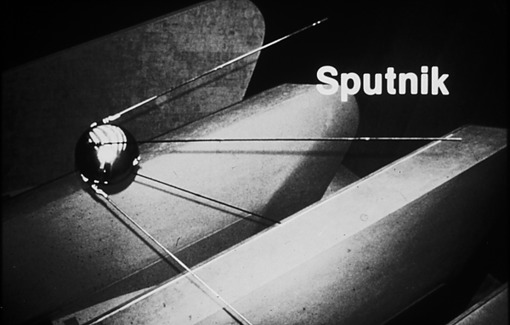

For most historians the story of the Internet began with satellite Sputnik. A metal ball, 58 cm in diameter, that sent out acoustic signals in the form of simple beeping. Yet that is just one part of the story. From a territorial perspective, this story marks the beginning of inter-networking in the US, which started with great disappointment as the initial event did not take place on their native soil but thousands of miles away. Leninsk, in Kazakhstan, was where the Sputnik satellite was launched and Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin started his journey as first man in outer space five years later. Leninsk was renamed Baikonur in 1995, and it is from here that Russian spaceflights have been taking off ever since.

In 1957, an event like the Sputnik launch needed explaining, not least because of Cyrillic script suddenly appearing in the US media, or the severe undermining of American scientists’ self-esteem. President Eisenhower believed that it was the USA’s inherent destiny to be the first conquerors of the universe. For the USSR to steal such a march as Sputnik represented was unthinkable. After all it was the United States of America whose scientists developed the atomic bomb first, and its nuclear-powered submarine Nautilus was diving deep under the Greenland Icecap. The latter should be remembered as a proof of “remarkable benefits due to mankind from peaceful uses of atomic power”. That is what William R. Anderson, captain of the Nautilus, told the media on his return in 1958.

For US politicians, Sputnik was a wake-up call. The event served the science committee as an excuse to ask for a larger money pot. New labs such as ARPAG (the D for Defence was added in 1972) and NASA were funded, and calls were made for a “re-evaluation of engineering education”.

“In the post-Sputnik period, beginning in the late 1950s, engineering schools emphasised quantitative, analytical skills even more. Accompanied by a strengthening of mathematics requirements.”

International Competitiveness in Electronics, Washington, D. C., U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, OTA-ISC-200, November 1983.

Media played their role well by supporting the concept of a threatening sky. The meme that was finally implanted in the collective mind was one that described the nation’s pride and an unknown war: nuclear war. Viewed in hindsight, one might conclude that it was rather strange that a mere piece of metal could have had such an affect. Yet one cannot deny that this occurred in the United States.

One treaty and six fountain pens

In Europe, the story of networking began differently, even though it carries the same time stamp. In 1957, the key place for Europeans was not Leninsk, but Rome, in Italy. Europe was still sunk deep into a fiscal black hole, licking the wounds caused by World War II.

Six European politicians and their advisors appeared before the cameras on 25 March 1957. Seated in a magnificent room, they signed a piece of paper. The image handed down over decades is not one of technology or conquering, but of technocracy, and a desire for peace.

Two opposing attitudes

In the US, the headline of the time was: “Never Again”, which can be read to mean never again to come second in a scientific race. In Europe, the notion “never again” was also hailed, not in relation to science or engineering, but about war.

Like the Sputnik launch, signing the Treaty of Rome was a milestone. Yet in contrast to the US, neither the European technocrats nor the mainstream media found it especially necessary to explain to the public what the treaty meant, in a language everybody could understand.

“Now, somehow, in some way, the sky seemed almost alien. I also remember the profound shock of realising that it might be possible for another nation to achieve technological superiority over this great country or ours.”

Lyndon B. Johnson, then US Senate Majority Leader

In contrast, Sputnik was branded a sensation: a great media event, as well as a world political affair which fired the general imagination. Even if one takes into account the time – the conservative 1950s with its belief in hierarchies, and command and control structures (the early twentieth century had witnessed two cruel world wars), one can already identify a red line which endures today: Compared to the US, Europe has a marketing and management problem to solve rather than a scientific one.

“There has always been nationalism in anything technical.”

Peter Kirstein, computer scientist. 2003

Continue reading at SCIENCEIn hindsight, one might conclude that the Treaty of Rome conferred the Nobel Peace Prize on Europe in 2013 while Sputnik helped the USA to gain supremacy over the Internet and data in general. Though this is short-sighted thinking, as there is always more to a story than one can digest at first glance. However, for a moment, let’s conclude just that.