Technology is always also politics

“There has always been nationalism in anything technical.” (Peter Kirstein, 2003)

In the development of computer networking, differences may have arisen between the USA and Europe yet there are also similarities worth mentioning; for example, the assumption that future economic growth will be strongly tied with technological advancement.

This idea has been incessantly repeated by politicians and industry analysts worldwide since the 1950s, but every new generation likes to think that they have gained new insight by rehashing exactly the same concept – most recently Philipp Rösler (b. 1972), Minister for Economy and Technology in Angela Merkel’s government (2011 - September 2013).

In May 2013, he suddenly discovered that the future lies in a digitalised world, and flew off to Silicon ValleyG with a flock of German companies in tow. (“Zukunft in digitaler Welt”, mo:ma, morgenmagazin, ZDF, 17 May 2013.)

A lasting case of déjà vu.

It is not enough to pick an old argument and hope that this time it will have an impact. More is needed to ensure progress than simply forecasting the market value of technological innovations.

1964, OECD Report: “There exists an association between economic and productivity growth and Member countries’ performance in the diffusion of technological innovation” (OECD, Gaps in Technology) (EU: 6 members states)

1972, Pierre Aigrain, French Ministry of Scientific and Industrial Development, CERN dinner speech: “The computer market has been expanding world-wide at the rate of about 30% per year.” (EU: nearly 9 member states)

1987, Green Paper, COM (87) 290 final: “By the year 2000, two thirds of the GDP of advanced countries will be generated in strongly information-related activities.” (EU-12)

2010, Digital Agenda, 17 May: “Half of European productivity growth over the past 15 years has been driven by information and communications technologies. “(EU-27) (Commission Report, Press Release)

2013, Davos, WEF Report: “What has become increasingly clear… is the role that information and communications technologies (ICTs), specifically digitisation, play in the potential development and maintenance of absolute advantage.” (EU-27)(WEF Global IITR Report 2013)

In the 1960s, that sort of comparison was also criticised. For example, Roger WilliamsP emphasised that this techno-economic analysis was once simply introduced as a “legal drafting exercise” in order to expand the EECG agenda of cooperation into the field of technology and science. This is a domain that is not addressed in the Treaty of Rome.

“Most attempts to overcome these difficulties have relied upon a putative connection between technology and economic growth. The argument has been that if this connection is accepted, then under Article 235 of the Treaty of Rome, the Commission may extend its powers to scientific and technological matters in pursuit of the objectives of the Treaty, particularly the objectives of economic development and cooperation laid down in Articles 2 and 4.”

Source: N.H. Aked, P.J. Gummett, “Science and technology in the European Communities: the history of the cost projects”, Research Policy 5, 1976, p. 284.

At least today, 50 years later, with cyber-war and information control in the spotlight, one should add to the equation that there is always a price tag attached to technological achievements and to technological dysfunction. The latter often means additional cost.

One message fits all: nuclear power

After Sputnik’s launch in 1957, US President Dwight D. Eisenhower called for immediate action. The public, alerted to the threat of an atomic attack from outer space began to dig nuclear fall-out shelters. New research labs like the ARPAG and NASA (both 1958) were funded, in order to encourage and fund scientists to boost innovation.

“ARPA was differentiated from other organizations by an explicit emphasis on “advanced” research, generally implying a degree of risk greater than more usual research endeavours.”

Source: Richard Van Atta, “DARPA, 50 years of bridging the gap”, United States Government, 2008.

Charles HerzfeldP adds another important point: it was very important for ARPA to have no enemies. But things changed when he left the agency in 1967.

European nations heard the news about the space race as well, but were still rebuilding Europe. Early on, the only case of fostering scientific research co-operation was, like the US, driven by particle physics: the CERNG laboratory, set up near Geneva 1954, with the financial support of twelve European countries. Then there was EURATOM, “to permit the advancement of the cause of peace.”

One further collaborative European action was agreed upon, which also has its office in politically neutral Switzerland. This initiative had nothing to do with science or with the recurrent belief of the time, namely that atomic energy was too costly for one nation to develop alone. Its purpose was – and still is today – to tell all western Europeans the same media story, to support the notion of a united Europe. Eurovision – as it is called by the EBUG – did not cover any scientist from CERN on its first broadcast on 6 June 1954, but rather Montreux’s daffodil festival. (To be fair, there was still precious little forthcoming from CERN’s laboratories.)

Both collaborations still exist today. Nobody denies that the science network won hands down over the media network. The only vestige now remaining of the public initiative for media unification is the annual Eurovision Song Contest while CERN has “one of the great engineering milestones of mankind”, the Hadron Collider

Good to know:

Still, every now and then, a political message is sent out by Europeans that there is a need for a medium that covers EU topics not just from the angle of national interests, but of union.

However, the main focus of the EEC 6 was the nuclear energy debate, with France eager to join the club of nuclear-weapons-wielding states behind the USA (1945), USSR (1949) and Britain (1952).

In the name of peace

It is worth recalling that in the post-war period West Germany faced a difficult challenge: it needed the EECG in order to be allowed to push its own high technology research in fields such as nuclear energy, the chemical industry and aerospace. By joining western European collaborative programmes it could do so in the name of peace.

It did not take long to persuade policy makers to combine forces in the field of nuclear energy, but it was a far greater challenge convincing all the EEC members that they would likewise have strength in numbers in other science and technology fields.

Continue reading at INDUSTRYFrance, on the other hand, was involved in nuclear energy research, but to make progress it required a supercomputer which could deal with the amount of data that particle physicists produced in their tests. The company of choice at the time was IBM, but the French order was put on hold by the United States government.

”Grounds for the embargo were that such computers could aid French nuclear weapons development, so delivery should be forbidden under the non-dissemination provisions of the Moscow Test Ban TreatyG.”

Source: John Walsh, “France: First the Bomb, Then the ‘Plan Calcul’”, Science, Vol. 156, 12 May 1967.

This may have been one reason why Charles de GaulleP was eager to gain independence, not just for military purposes, but also in the fields of science and computing. However, according to Maurice AllègreP, Plan Calcul, launched in 1965, was a plan to gain the latter.

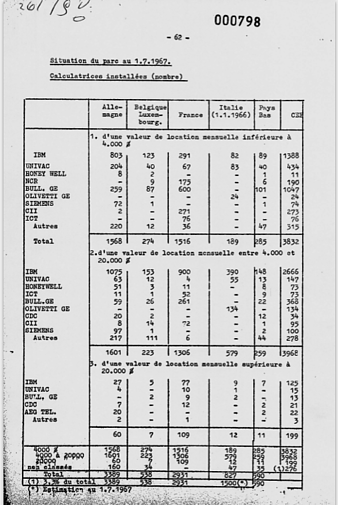

European computer market, 1967

The personal computer had not yet been invented, and computers cost a fortune. They were seldom bought, but licensed for a monthly fee. As can be appreciated in the table, it was a rare event for European computer manufacturers to do business outside their own home countries. Siemens, for example, had only five machines installed outside West Germany, while the French CII had 25. The opposite was true for US companies (GE, Honeywell, NCR and IBM). They already competed in a global market. Taking a close look into IBM’s books, it becomes clear what made the difference and scared European industry: by 1967, IBM had installed nearly the same amount of machines worldwide (70-75%), as within the USA (74%).

Source: Historical Archive of the European Commission, file BAC 38/1984, Year 1968-1969

The plan follows an idea which was first made a reality by the British. On one hand, they realised that their own computer market, which consisted only of orders from government and the military at the time, was too small. On the other, Harold Wilson wanted to enter the EEC, and one thing which was missing on the continent was a force in computing that might have sent an answer across the Atlantic towards IBM, world champion in the computing business at that time.

It was a real challenge to convince all six EEC members that they would likewise have strength in numbers in other science and technology fields such as nuclear energy and agricultural research.

Continue reading at INDUSTRY