Gaps in Technology and a Marshall Plan

What problem needs solving?

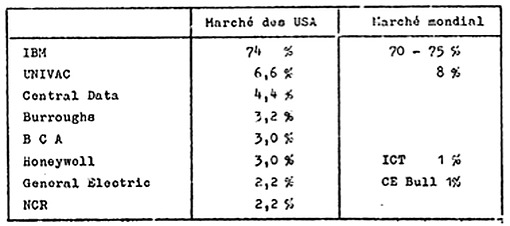

Experimentally driven research on “Future Networks” in Europe began in the mid-1960s. It was the result of the “technological gaps” discussion that emerged in Europe, shifting America’s leading role for utilising technology into the limelight.

It included both the analyses of the inherent nature of the technological gap and those of its economic, social and political causes and effects. The French author and journalist Jean-Jacques Servan–Schreiber, who influenced the discussions at the time with his bestseller “Le défi américain” (“The American Challenge”, 1967), couldn’t resist but comment the OECDG findings with the prediction that in

“Fifteen years from now the world’s third greatest industrial power, after the United States and Russia, may not be Europe, but American industry in Europe”.

Maurice AllègreP was not impressed: “The book was not written well, but it had its effect.”

However, the really surprising conclusion of the OECD ”General Report” was that Europe primarily had a management and structural rather than scientific problem to solve.

The reason for the technological gap in the 1960s was not a lack of willpower by nation states to invest in science and development – quite the opposite. The problem was that post-war Europe did not have the same amount of money at its disposal as the US.

“In fact the combined efforts of the four Western European countries for which data are available (United Kingdom, France, West Germany, Netherlands) do show some closing of the expenditure gap between 1958 and 1964, the United States index of Gross National Expenditure on Research and Development as a percentage of Gross National Product rising by a quarter and the “European” index rising well over 40%.”

Source: OECD General Report, 1968.

An expenditure of 40% of European GNP on Research and Development is a percentage scientists only can dream up today.

Meetings to develop a plan for a common technological and scientific policy have been held in Brussels since 1963. But one should not ignore the fact that the first documented reference to research interest dates back much further: To EURATOMG, which was on the ECSCG agenda in 1955. The hightime of nuclear science, which was anticipated to give rise to a new technological and industrial revolution …

”…which would extend to all sectors. The role which the atom was expected to fulfil was in many ways comparable with that played earlier by steam and that which information technology has actually had in the second half of the 20th century.”

Luca Guzzetti, A Brief History of European Union Research Policy, European Commission, Studies 5, October 1995.

Within the European Commission information technology had already been identified as another important field in which to combine forces. Yet, many years’ negotiation were needed to pave the way. As usual a committee was formed which was called “Comite de Politique Economique i Moyen Terme” (CPEMTG), followed by a subcommittee called PREST, Politique de Recherche Scientifique et Technologique, whose chairman was André MaréchalP, a French physicist.

Seen from the outside

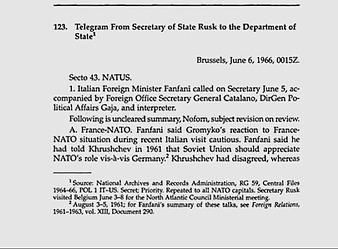

123. Telegram From Secretary of State Rusk to the Department of State, Brussels, June 6, 1966, 0015Z.

“U.S. felt it important that Western European technology advance, and sought means make U.S. technology available. President Johnson had recently sent Mr. Frutkin to Europe in this connection. Frutkin had found much interest in West Germany, almost none in UK, with Italy somewhere between.

U.S. spent 30 billion dollars on research and development for all purposes, Secretary continued. Although we recognized differences in industrial capacity, and difficulties of starting “Marshall Plan for Technology”, way had to be found.

Fanfani welcomed Secretary’s statement. He thought Marshall Plan for Technology would show possibilities inherent in Atlantic Community concept. Italians were impressed by almost unbridgeable gap between U.S. and European technology. They favored identifying specific areas for cooperation to integrate U.S. and European efforts. If UK indeed dropped out of ELDO [European Launcher Development Organisation], Italian Cabinet had agreed that Italy would do same, and would devote resources instead to national research. Most of shifted funds would go to send people to U.S. for study. Fanfani thought Marshall Plan for Technology would have great attraction also in France, even if not with De Gaulle. It would also find receptivity in Eastern Europe and thus promote coexistence.

C. U Thant. Secretary said U Thant would decide in June whether to serve as UN SecGen beyond present term. Although President Johnson in letter had urged him stay on, appeared strong possibility he would leave. Secretary foresaw great problems in finding successor in view Soviet veto power. He requested Fanfani as General Assembly President write U Thant urging him to stay on.

Fanfani said he had touched on subject with U Thant in Strasbourg but had learned little. He agreed to send letter now urging SecGen keep post.

Secretary thought U Thant motivated to leave UN by pressure from Ne Win, by family problems and by behind scenes Soviet pressure to exact concessions actions as price for supporting Thant’s continuation in office. Fanfani added as motive burden of UN financing question.

Fanfani thought family reasons might be overriding; suggested further exploration this motive. He thought former UN Deputy SecGen, Soviet national Milanya, who just ordained as Anglican priest, had spiritual ties with U Thant, and suggested Ralph Bunche could sound Milanya.

Fanfani added rumor was circulating that U.S. was opposed to U Thant’s continuation in office while Soviets supported it.

Secretary concluded by expressing hope for another talk with Fanfani before both left Brussels, to discuss Communist China and other matters.

As meeting broke up, Fanfani handed over aide-mémoire on Italian approach to EximBank concerning 45 billion lire purchase of supplies in U.S. for Fiat factories. Secretary observed problem was essentially technical, with no top-level political aspects. Text of aide-mémoire will follow septel. (Not found.)

Source: “Foreign Relations of the United States 1964-1968”, Vol XII, WesternEurope, US Dept. of State. Released by the Office of the Historian. (last visited 27 August 2013)

http://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v12/d123

The Marshall Plan was named after General George C. Marshall, and was more than just a foreign aid program. It was also an opportunity for US companies to expand their business area overseas. Furthermore, the roots of the foundation of the OECD can be traced back to 1948 and the Marshall Plan.

There was no shortage of ideas on how to push technological research within Europe: For example the Italian foreign minister Amintore Fanfani proposed a “technological Marshall Aid” scheme. An idea that found favour in the US, as it also implied a surplus for US computer companies.

The Italian plan was shortly followed by a British proposal for a European Technological Community, as part of the EECG. Yet, no agreement was reached on that matter.

Best game in town: searching for names

Instead, the EEC decided to address this problem by setting up a new working group within the medium-term Economic Policy Committee by March 1965. The name of this group changed several times, it is best known as the PREST group.

“I tried to find a name and I proposed calling The Group Politique de la Recherche Européenne Scientifique et Technique Organisée – PRESTO. Well, they dropped the “O” so it is a PREST Group, and the Group has been looking at what we are doing in the various countries of Europe to find new areas of cooperation.”

Source: Pierre Aigrain, “Computing and scientific research in Europe”, Computer Physics Commmunications 3, Supplement, pp. 166-173, North-Holland Publishing Company, 1972.

On 31 October 1967, the first PREST report was presented to the Commission. It emphasised once more the economic importance of R&D, and the need to optimise the overall use of resources through cooperation, which should be enlarged to non-EEC member states. The idea was to install a united research policy instead of reaching ad hoc agreements solely between individual states. This is a brief that sounds familiar, even in 2013.

“[…] to examine the problems involved in developing a co-ordinated policy for scientific and technological research, bearing in mind the possibility of co-operations with non-member countries.”

Source: “Lucca Guzzetti, A Brief History of European Union Research Policy”, European Commission, Studies 5, October 1995.

USA & Europe: one conclusion, two styles

After more than 10 years of debate on whether and how to unite Europe in the area of science and research – a debate largely driven by a lack of money – seven areas of cooperation were finally identified and agreed upon at the EU Council. PREST was given the mandate to investigate the feasibility of fields such as information sciences, telecommunications, transport, metallurgy, meteorology, oceanography and the control of environmental pollution.

At ARPA research teams investigated the field of information science in order to study command and control but also communication structures. The department for the latter was the IPTO, which was led by Robert Taylor at the time. Metallurgy, for example had been an area of interest for ARPA since 1963.

Charles HerzfeldP, then deputy director, was one physicist who was especially interested in that sort of interdisciplinary work. The hope was that new findings in metallurgy could bring down the production costs of computers. Rightly so. As scientists discovered how to produce silicon more cheaply, the semiconductor industry flourished. Research funding in meteorology covered the financial need for satellite research. Oceanography meant investing in submarines and nuclear test detection.

It comes as less of a surprise that the topics chosen by the PREST group were also on the agenda of the US Advanced Research. Nevertheless, in Europe the call for proposals became a political affair. Even though all nations agreed upon the necessity of strengthening forces in order to close the technological gaps, the Six picked a new quarrel: which non-EEC member should be allowed to join the party? Who should be allowed to write proposals? Only the EEC Six? Should the candidate countries at the time – UK, Denmark, Norway and Ireland – be included? Should the three neutral, industrialised nations of Austria, Sweden and Switzerland be included? These were the hot topics of debate for PREST members in autumn 1967.

Furthermore, there was French President, Charles de GaulleP. According to de Gaulle’s vision, Europe stretched from the Atlantic to the Urals. Any enlargement of the EEC northwards or westwards to admit the British and Scandinavians was not in his interest.

As if that weren’t enough for causing delays, the situation collapsed for André Maréchal’s team once and for all in winter 1967. Charles De Gaulle thwarted entry of the UK to the EU again, having already done so in 1962.

“There has always been nationalism in anything technical.” (Peter Kirstein, 2003)

Continue reading at SCIENCEBut contrary to 1962, de Gaulle now faced some muted protest: Italy and the Netherlands decided to stay away from the next scheduled PREST meeting. In hindsight this may seem strange given the fact that the EEC agenda contained far more important meetings. The effect was a further delay in the already cumbersome negotiations within PREST. For André Maréchal it was one delay too far. He was fed up and resigned from PREST. As it always happens at these sort of affairs another chair needed to be found. About one year later, the “Maréchal Group” became the “Aigrain Group”, after French physicist Pierre Aigrain, who took over the lead. It seemed after all that nobody could ignore the French.

Slow process and vanishing interest

Changing names:

PREST was called the “Maréchal group” (1965 - 1967) and the “Aigrain group” (1968 − 1969).

In the early 1970s, it was renamed Comité de la Recherche Scientifique et Technique (CREST).

Thirty years later CREST became the European Research Area Committee (ERAC).

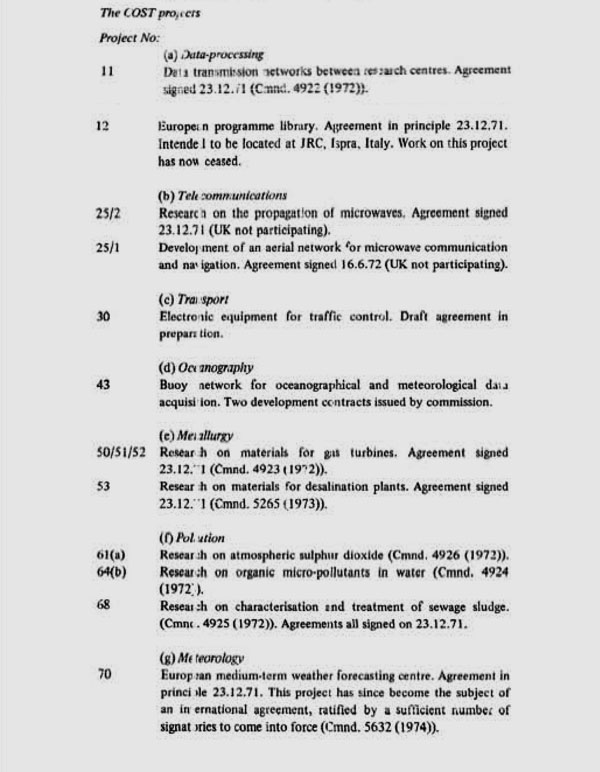

A spin-off of PREST was the Cooperation Europeenne dans la Domaine de la Recherche Scientifique et Technique (COST), whose agenda was outlined in 1969.

West Germany did not like the idea of expanding the EEC research policy across the borders of the first six member states. In late 1969, a decision was made by PREST that a committee should be founded to coordinate European research efforts. It was named COST, Coopération Européenne dans la Domaine de la Recherche Scientifique et Technique, and it was established to boost science and technology cooperation and gain strength by including non-EEC members as well. The initial projects under this umbrella had already been decided upon and re-formulated: data processing, telecommunications, transport, oceanography, metallurgy, pollution and meteorology seemed to be the priorities of EEC members on expanding research and funding.

The Cost projects

Source: “N.H. Aked, P.J. Gummett,

“Science and technology in the European Communities: the history of the cost projects”, Research Policy 5, 1976, p. 284

West Germany agreed with these areas, but not with the process. For the German representative Fritz Hellwig, the idea of bringing too many people into the discussion simply appeared to be counter-productive. In autumn 1969, he stated in an internal memo that he did not consent to increasing member numbers. He insisted that there had to be a limitation on the number of participating countries in order to ensure work effectiveness. He accepted the four candidate countries (Norway, Denmark, the UK and Ireland) and also the three industrialised neutrals (Austria, Sweden and Switzerland) but that ought to be enough.

“These countries can contribute effectively to most of the proposed actions, and they are already participating in important tasks of European cooperation.”

Source: M. Hellwein, “Cooperation Technologique – PREST – Etat d’advancement des Travaux”, 10 October 1969, Historical Archive of the European Commission, Brussels, SEC (69)3760, file BAC 86.

However, things turned out differently. Spain and Portugal were also invited to participate in COSTG projects, and in 1971 four additional members were added: Finland, Greece, Turkey and Yugoslavia. Thus, there were 19 countries participating in various project groups and tenders. In hindsight it appears that the solution that was found was a compromise: only the six member states were allowed to bring in proposals. Non-member states merely received a copy of the document afterwards and could articulate their interest in what was decided.

According to the PREST reports, 47 proposals were first discussed in the “Aigrain Group” in 1968, according to the seven pillars, which had been allocated by the Council at a meeting on 31 October 1967. Two years later, EEC permanent representatives only showed interest in 30 projects, which were reduced to just 17 projects by 1971. The argument was that these were the only ones of public interest.

“Commenting in early 1971 on the impact of the Aigrain report, PREST observed that only seventeen of the original forty-seven proposals were still under active consideration, a disappointing return for an expenditure of 2 million Units of Account and 12 500 man days.”

Source: Le Monde, 23 November 1971, in: N.H. Aked, P.J. Gummett, “Science and technology in the European Communities: the history of the cost projects”, Research Policy 5, 1976, p. 284.

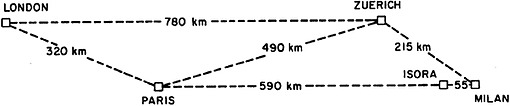

In the case of computer networking, one project number is certainly of interest: “COST Project 11”G, the European Informatics Network (EIN). It was set up as a European international research project to study informatics network techniques. This was a project that also West Germany was participating in with an associated Centre in Darmstadt (GMD). Yet “COST Project 11” was almost over before this specific UN treaty was signed also by West Germany in 1976.

A multinational treaty was signed on 23 November 1971 by ten nation states and the European Atomic Energy Community. Coming soon. We received some new facts and figures, and for sure want to re-check them first. Stay tuned!

Continue reading at SCIENCE